What Your Upper Cervical Correction Is Actually Doing to the Brain, the Brainstem, and the Dura

There is a small cluster of muscles at the base of your skull that contains up to 500 neuromuscular spindle cells per gram of tissue. The large paraspinal muscles of your lumbar spine contain roughly 3 to 5. Your quadriceps, responsible for extending the knee against significant load, contain fewer still. The suboccipital muscles are not prime movers. They were never designed to be. They are sensory transducers, and the signal they generate continuously is feeding some of the most consequential neurological regulation in the human body. [1]

Every PRYT correction you make is working directly on this tissue. The clinical results you observe afterward, including hip range of motion changes, autonomic shifts, visceral tone changes, and blood pressure normalization, are not coincidental findings. They are mechanistically predictable once you understand what this tissue is actually connected to and how those connections work.

This is that explanation.

Ia and Ib Fibers: Two Signals, One Neighborhood, Multiple Destinations

Inside each muscle spindle, intrafusal fibers are innervated by two types of afferent neurons. The Ia fibers wrap around the nuclear bag and chain fibers as primary annulospiral endings. They respond to both the rate of change of muscle length and its absolute length simultaneously, making them exquisitely sensitive to dynamic stretch. [2] Firing rates in Ia afferents encode velocity information with remarkable precision, sending continuous real-time data about movement quality into the central nervous system. They are not simply reporting position. They are reporting the quality and dynamics of movement as it unfolds in real time.

The Ib fibers innervate the Golgi tendon organs sitting in series with the muscle at the musculotendinous junction. They encode tension, not length. [3] When contractile force rises, Ib firing increases, activating inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal horn that suppress alpha motor neuron drive to the agonist and facilitate the antagonist. This is autogenic inhibition, and it is the mechanism you are recruiting during PRYT corrections when you resist your patient's maximal isometric contraction.

But here is where the standard explanation requires updating.

Recent evidence shows that GTO-driven autogenic inhibition is transient. The inhibitory effect lasts only as long as the active contraction itself. [3] It does not account for the prolonged range of motion changes and tone shifts you observe clinically after a PRYT correction. The Ib pathway is also context-dependent. During different movement conditions, inhibitory Ib pathways can become excitatory. [4] You are not producing a simple fixed suppression of motor output. You are reconfiguring the reflex pathway itself based on the movement context you created.

Gamma motor neurons are the efferent arm of spindle sensitivity regulation. They innervate the intrafusal fibers and set the mechanical sensitivity of the spindle. [5] After a maximal isometric contraction, gamma motor neuron activity does not simply return to baseline. It undergoes complex re-tuning that changes the threshold for subsequent stretch reflex activation. [6] The spindle establishes new operating parameters.

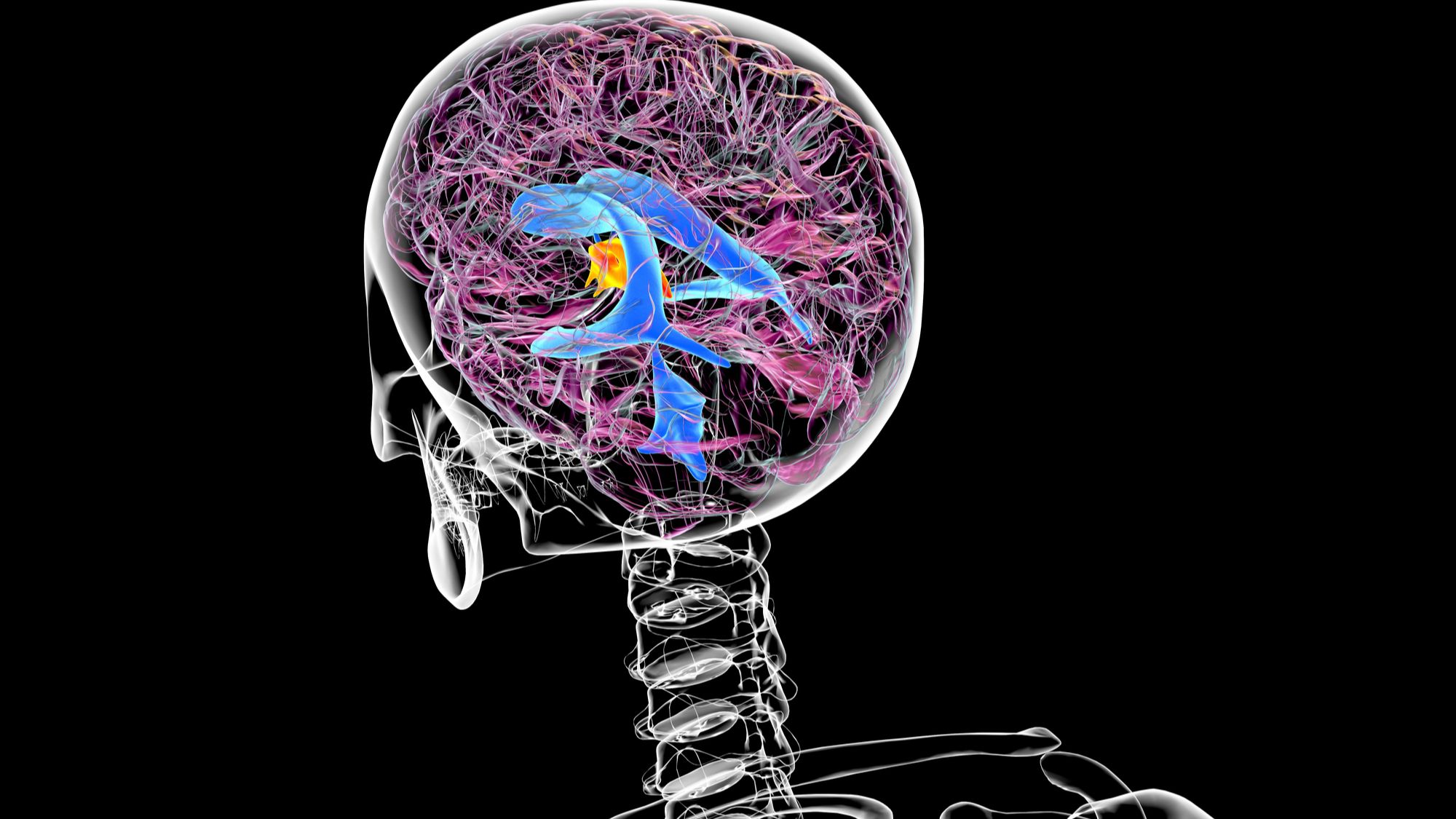

In the suboccipital musculature, this Ia and Ib signaling is not managing local joint mechanics alone. It is feeding simultaneously into the spinocerebellar tracts, the vestibular nuclei, the trigeminal sensory complex, and through the spinosolitary tract, directly into the brainstem autonomic regulatory neighborhood. [7, 8] The spindle density means the signal-to-noise ratio from this tissue is extraordinarily high. When that signal is corrupted by a fixation or subluxation pattern, you are introducing systematic error into multiple integration systems at once. When you correct it, the lasting effect is not primarily local. It is the downstream recalibration of those systems that produces the clinical changes you see.

The Cerebellar Integration Loop

The cerebellum operates as a predictive comparator. It receives efference copies of motor commands from the cortex, then compares intended movement against actual sensory feedback arriving via the spinocerebellar tracts. [9] Discrepancies generate error signals processed through the deep cerebellar nuclei, primarily the dentate and interposed nuclei, and sent back through the thalamus to the motor cortex and directly to the red nucleus in the midbrain tegmentum. [10]

The interposed nucleus deserves specific attention here. Research has identified two distinct neuronal populations within the cerebellar interpositus nucleus where vestibular and proprioceptive signals converge. [11] One population carries traditional vestibular signals describing head movement in space. A second population precisely matches vestibular against proprioceptive signals, functionally canceling each other during combined sensory stimulation. This second population encodes body motion in space, not just head motion, providing the reference signal for controlling limb movements throughout the body. [11]

This is the anatomical basis for why PRYT tests two body parts simultaneously. You are stress-testing this integration system. You are asking the interposed nucleus to reconcile proprioceptive input from two ends of the body at once. When the integration fails and an indicator muscle weakens, you have found a fault in that reconciliation process.

The rubrospinal tract originates from the magnocellular red nucleus and projects to cervical and upper limb motor circuits. In humans, the magnocellular portion of the red nucleus is significantly reduced compared to other mammals, [12] and the rubrospinal tract is not the dominant descending motor pathway it is in quadrupeds. But the red nucleus in humans has taken on a different and arguably more sophisticated role: integrating action plans with reward and motivational signals, showing stronger functional connectivity with action-mode and salience networks than with motor-effector networks directly. [13]

The reticular formation is the more clinically relevant downstream pathway for the postural tone changes you observe. [14] It coordinates eye and head movements while simultaneously regulating postural muscle tone through excitatory and inhibitory pathways, and it supports anticipatory postural adjustments throughout the body. Improved proprioceptive input from the upper cervical complex, feeding through the interposed nucleus and into the reticular formation, changes postural tone in the limbs. That is why the hip opens after you correct the neck. You did not touch the hip. You fixed the reference signal feeding a system that governs tone throughout the body.

The Vestibulo-Ocular Story and Why Roll Is Different

The vestibular nuclei receive convergent input from three sources: the semicircular canals and otolith organs via cranial nerve VIII, upper cervical proprioception via direct cervical afferents, and visual input via the superior colliculus. [15] This convergence is the anatomical basis for the vestibulo-ocular reflex and the cervico-ocular reflex, which work together to stabilize gaze during head movement.

The cervico-ocular reflex gain is typically small in healthy individuals but becomes more prominent in pathological conditions. [16] Research on cervicogenic dizziness shows distinct abnormalities in cervical proprioceptive input that correlate directly with impaired visual-vestibular central integration. [17] The dysfunction is not in the eyes or the vestibular apparatus. It is in the cervical proprioceptive signal corrupting the integration.

The roll test is positive when pelvic and lumbar rotation creates a proprioceptive conflict that the vestibular integration system cannot resolve cleanly. When the patient lateralizes their eyes, they are activating the visual righting reflex through the vestibulo-ocular pathway, altering the gain of cervico-vestibular integration. [15] Importantly, research confirms that oculomotor signals alone, without the visual component, do not directly influence postural control. [18] The visual input is essential to the correction mechanism in the oculobasic protocol. In approximately 70% of positive roll cases, therapy localizing the sacrum alone resolves the indicator muscle weakness. The remaining 30% represent cases where the visual righting reflex is genuinely integrated into the dysfunction pattern and require the full oculobasic protocol.

The Jugular Foramen: Two Mechanisms, Not One

The jugular foramen sits at the junction of the occipital and temporal bones. [19] Through it passes the vagus nerve, the glossopharyngeal nerve, and the spinal accessory nerve. The vagus and spinal accessory nerves share a large posterior adipose column within the intraforaminal extradural neural axis compartment, separated from the glossopharyngeal nerve by a fibrovenous curtain of meningeal dura. [20]

This compartment arrangement has a direct clinical implication most practitioners have not connected. When you find spinal accessory nerve dysfunction affecting sternocleidomastoid and trapezius tone in a patient who also presents with autonomic findings suggesting reduced vagal tone, they may be sharing a common mechanical cause in that dural compartment. They are anatomical neighbors in the most literal sense.

The rectus capitis lateralis runs immediately anterior to the neurovascular structures at the jugular foramen level. [21] The superior oblique and rectus capitis posterior muscles border the same region. [22] These are the muscles you are directly addressing with PRYT examination and correction. Decreased elasticity of the sternocleidomastoid muscle can restrict vagal nerve movement and predispose to entrapment with downstream neuroinflammation and dysfunction. [23]

Physical entrapment is mechanism one. Sustained mechanical tension from a fixation pattern, fascial restriction from chronically hypertonic suboccipital musculature, or postural strain from a positive yaw 1 or pitch pattern can all create low-grade compression on the vagus as it exits the skull. [24] This does not require gross pathology. It requires only the chronic, low-level tissue tension that accompanies a subclinical fixation pattern.

Mechanism two is neurological and may be more clinically significant.

The Nucleus Tractus Solitarius and the Signal Quality Problem

The nucleus tractus solitarius occupies the dorsomedial medulla oblongata. It is the primary termination site for vagal afferent fibers arriving from the heart, lungs, great vessels, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and proximal colon. [25] It also receives input from the glossopharyngeal nerve, the trigeminal nucleus, and from upper cervical spinal cord levels via the spinosolitary tract. [26]

The NTS does not simply relay information. It functions as a comparator, evaluating error signals between descending neural projections and cardiovascular receptor afferents, then projecting to nuclei that regulate circulatory variables. [27] It modulates the gain of vagal reflexes. It regulates gastric secretion and motility through glutamatergic transmission to the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. [28] It coordinates respiratory rhythm through connections with the pre-Botzinger complex. It communicates bidirectionally with the hypothalamus and limbic system through the central autonomic network.

Different vagal populations project to specific NTS subnuclei with differential termination patterns. [29] TRPV1-expressing afferents terminate in medial regions near the caudal obex. [30] 5-HT3 positive afferents terminate in ventral and lateral regions throughout the rostral-caudal medulla. [29] This anatomical organization means different visceral functions are regulated through anatomically distinct circuits within the same nucleus. A disruption in the NTS neighborhood does not produce one uniform autonomic effect. It produces a pattern of effects depending on which circuits are most affected.

This explains the clinical variability you observe post-correction. Some patients show ICV tone changes. Some show blood pressure normalization. Some show gastric pattern shifts. Some show respiratory changes. The NTS subnuclei organization gives you a mechanistic reason for why the pattern differs between patients. You are not producing one effect. You are improving signal quality in a neighborhood where multiple specific circuits are running simultaneously.

Upper cervical proprioceptive input arrives into this regulatory environment continuously via the spinosolitary tract. In a normally functioning system, that input is part of the sensory context the NTS uses to calibrate autonomic reflex gain. In a system with chronic upper cervical fixation patterns, that input is dysregulated, excessive, or temporally disordered. The NTS is receiving noise from one of its primary input channels and integrating that noise into its regulatory output across all of those circuits simultaneously.

The clinical confirmation of this is now in the literature. Post-isometric muscle energy techniques applied to the upper cervical spine at OA, AA, and C2 produce statistically significant increases in RMSSD, pNN50, and high-frequency HRV power. [31] Parasympathetic tone measurably shifts after upper cervical correction. Manual cervical correction produces concurrent reductions in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure through documented autonomic modulation. [32] These are not theoretical outcomes. They are measured.

The Myodural Bridge: The Finding That Changes Everything

The myodural bridge complex is a dense fibrous connective tissue structure connecting the suboccipital musculature directly to the spinal dura mater. [33] It passes through the posterior atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial interspaces. Its fibers consist primarily of type I collagen arranged in parallel orientation, designed specifically to transmit strong tensional forces from muscle contractions to the dural sheath. [34]

The posterior atlanto-occipital membrane, the atlanto-axial membrane, and the dura mater develop from a common mesenchymal origin between weeks 11 and 14 of fetal development. [35] They are not separate structures that happen to be adjacent. They share a developmental lineage and form a functional continuum. Fixation patterns at the occiput-atlas-axis complex are problems in a continuous tissue system that includes the dura itself.

The myodural bridge contains four types of sensory receptors embedded within its own fibers: Ruffini corpuscles distributed perivascularly, Pacinian corpuscles near the dura and muscle attachments, Golgi-Mazzoni corpuscles, and widely distributed free nerve endings. [36] The bridge is not only transmitting mechanical force to the dura. It is itself a proprioceptive organ participating in the same sensory signaling network you are addressing with PRYT.

The atlantodural and axiodural ligaments extend from the posterior arch of C1 and the lamina of C2 directly to the dura, creating a thickened dural region at the C1-C2 level. [37] The vertebrodural ligament links the posterior atlas-axis region to the dural sleeve. [38] These are not anatomical curiosities. They are the structural reason why atlas and axis fixation patterns have dural consequences.

The CSF implications are direct and documented. Electrical stimulation of the obliquus capitis inferior, a muscle you address with PRYT correction, produced measurable CSF pressure increases at multiple intracranial locations. [39] Head rotation transmitted through the myodural bridge increased maximum CSF flow rates and stroke volumes during ventricular diastole. [40] The occipital pole showed the earliest pressure response, with waves propagating through the subarachnoid space and ventricles. [39]

The myodural bridge functions as a physiological pump for CSF circulation. [40] Head movement generates mechanical forces transmitted through the bridge to the dura, creating pressure waves that facilitate CSF movement. When suboccipital muscle function is altered by chronic fixation patterns, CSF secretion rates and intracranial pressure are affected. [41] Surgical severance of the bridge decreased intracranial pressure. Hyperplasia from chronic dysfunction increased it. [42]

Chronic upper cervical fixation patterns are not just neurologically disruptive. They may be progressively altering the mechanical properties of a dural system that drives CSF circulation through the craniocervical junction. [43] The sphenobasilar fault patterns and inspiration-expiration faults you recheck after PRYT correction are not separate findings. They may be downstream expressions of a dural mechanical system that your correction just changed.

Apply

Clear the rocker motion fixation before you test any PRYT pattern. The rocker addresses occiput-on-atlas and atlas-on-occiput fixations as isolated movements in every direction. If those are present, your module integration tests are reading through dysfunctional tissue in the most proprioceptively dense and neurologically consequential region of the body. Your PRYT findings will be incomplete or misleading. Rocker is the prerequisite, not the optional add-on.

When you correct a positive upper cervical PRYT pattern, your recheck is not optional and it is not just confirmation. You have changed the mechanical environment of the myodural bridge. You have altered the proprioceptive signal quality feeding the cerebellar comparator, the reticular formation, and the spinosolitary input to the NTS. You have changed the fascial tension environment at the jugular foramen. Find what moved.

Recheck ICV tone. Recheck hiatal hernia patterns. Recheck sphenobasilar fault. Recheck inspiration and expiration faults. Check blood pressure if you have the equipment. Assess heart rate variability if you can measure it. Look at hip range of motion before and after and document it.

The correction takes thirty seconds. The downstream effects are systemic and they are real.

References

- Hallgren RC, Rowan JJ. Implied Evidence of the Functional Role of the Rectus Capitis Posterior Muscles. De Gruyter. 2020.

- Oliver KM, Florez-Paz D, Badea T, et al. Molecular correlates of muscle spindle and Golgi tendon organ afferents. Nature Communications. 2021.

- Moore M. Golgi Tendon Organs: Neuroscience Update with Relevance to Stretching and Proprioception in Dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2007.

- Hamm T. Charting intermuscular reflex pathways with an effective force stimulus. Journal of Physiology. 2019.

- Dimitriou M. Crosstalk proposal: There is much to gain from the independent control of human muscle spindles. Journal of Physiology. 2021.

- Dideriksen J, Negro F. Feedforward modulation of gamma motor neuron activity can improve motor command accuracy. Journal of Neural Engineering. 2021.

- Pop IV, Espinosa F, Blevins CJ, et al. Structure of Long-Range Direct and Indirect Spinocerebellar Pathways as Well as Local Spinal Circuits Mediating Proprioception. Society for Neuroscience. 2021.

- Eneanya CI, Smith GM. The Sensory Input from the External Cuneate Nucleus and Central Cervical Nucleus to the Cerebellum Refines Forelimb Movements. Cells. 2025.

- Boisgontier M, Swinnen S. Proprioception in the cerebellum. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014.

- Beitzel CS, Houck BD, Lewis SM, Person AL. Rubrocerebellar Feedback Loop Isolates the Interposed Nucleus as an Independent Processor of Corollary Discharge Information in Mice. Society for Neuroscience. 2017.

- Luan H, Gdowski MJ, Newlands S, Gdowski G. Convergence of Vestibular and Neck Proprioceptive Sensory Signals in the Cerebellar Interpositus. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013.

- Stacho M, Husler AN, Brandstetter A, et al. Phylogenetic reduction of the magnocellular red nucleus in primates and inter-subject variability in humans. Frontiers Media. 2024.

- Krimmel SR, Laumann TO, Chauvin R, et al. The human brainstem's red nucleus was upgraded to support goal-directed action. Nature Communications. 2025.

- Viseux F, Simoneau M, Pamboris GM, et al. The Reticular formation: An integrative network for postural control. Neurophysiologie clinique. 2025.

- Swain S, Dubey D. Vestibulo-ocular reflex: A narrative review. Matrix Science Medica. 2023.

- Ooka T, Honda K, Tsutsumi T. Static cervico-ocular reflex in healthy humans. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 2023.

- Gao Y, Wang X. Correlation of Abnormal Cervical Proprioception with Visual-Vestibular Interaction Dysfunction in Cervicogenic Dizziness. Journal of Contemporary Medical Practice. 2025.

- Wang YR, Bacon B, Maheu M, Champoux F. Oculomotor stimulation without visual input has no impact on postural control. NeuroReport. 2021.

- Mode K, Murawska A, Janda P, et al. Variability and surgical anatomy of jugular foramen. Folia medica Cracoviensia. 2025.

- Bond JD, Xu Z, Zhang M. Fine configuration of the dural fibrous network and the extradural neural axis compartment in the jugular foramen. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2020.

- Basma J, Parikh K, Khan NR, et al. Simplifying the Surgical Classification and Approach to the Posterolateral Skull Base and Jugular Foramen Using Anatomical Triangles. Cureus. 2021.

- Park H, Yoo J, Oh HC, Froelich S, Lee KS. The Anterolateral Approach, Revisited for Benign Jugular Foramen Tumors. Operative Neurosurgery. 2023.

- Özel Aslyçe Y, et al. Comparison of sternocleidomastoideus flexibility, vagus nerve function, and gastrointestinal symptoms in chronic neck pain and healthy individuals. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2023.

- Liang L, Qu LC, Chu X, et al. Meningeal Architecture of the Jugular Foramen. World Neurosurgery. 2019.

- Andresen M, Doyle M, Bailey TW, Jin YH. Differentiation of autonomic reflex control begins with cellular mechanisms at the first synapse within the nucleus tractus solitarius. 2004.

- Boyle R. Medial and lateral vestibulospinal projections to the cervical spinal cord of the squirrel monkey. Frontiers in Neurology. 2025.

- Zanutto S, Valentinuzzi M, Segura ET. Neural set point for the control of arterial pressure: role of the nucleus tractus solitarius. BioMedical Engineering OnLine. 2010.

- Clyburn C, Browning K. Glutamatergic plasticity within neurocircuits of the dorsal vagal complex and the regulation of gastric functions. American Journal of Physiology. 2021.

- Kim SH, Hadley S, Maddison M, et al. Mapping of Sensory Nerve Subsets within the Vagal Ganglia and the Brainstem. Society for Neuroscience. 2020.

- Doyle M, Bailey TW, Jin YH, Andresen M. Vanilloid Receptors Presynaptically Modulate Cranial Visceral Afferent Synaptic Transmission in Nucleus Tractus Solitarius. Society for Neuroscience. 2002.

- Miller A, Curran C, Fanous S, et al. Autonomic Rehabilitation: Cardiovagal and Autonomic Impacts of Post Isometric Muscle Energy at the Upper Cervical Spine. AAO Journal. 2025.

- Shishonin AY, Vetcher A, Pavlov VI. Influence of the method of manual-physical correction on autonomic regulation in patients with essential arterial hypertension. Voprosy kurortologii. 2024.

- Yang H, Song X, Yue C, et al. Identification, structural features, and potential functional significance of the myodural bridge in African clawed frog. Scientific Reports. 2025.

- Jiang WB, Zhang ZH, Yu SB, et al. Scanning Electron Microscopic Observation of Myodural Bridge in the Human Suboccipital Region. Spine. 2020.

- Rodríguez-Vázquez J, et al. Morphogenesis of myodural bridges: A histological study in human fetuses. Cells Tissues Organs. 2025.

- Song MD, Sui HJ, Zhang JF, et al. Optimizing head movement patterns to maximally modulate CSF flow by myodural bridge complex. Medicine. 2025.

- Iwanaga J, Reina MA, Hama S, et al. The Cervical Ligamentum Flavum and Cervicodural Ligaments. Spine. 2026.

- Zheng N, Yuan XY, Li YF, et al. Definition of the To Be Named Ligament and Vertebrodural Ligament and Their Possible Effects on the Circulation of CSF. PLoS ONE. 2014.

- Yuan XY, Yang KQ, Ma Y, et al. Temporal and spatial variations in CSF pressure are influenced by electrical stimulation of the OCI muscles in beagles. Scientific Reports. 2025.

- Xu Q, Yu SB, Zheng N, et al. Head movement, an important contributor to human cerebrospinal fluid circulation. Nature Portfolio. 2016.

- Yang H, Wei XS, Gong J, et al. The relationship between myodural bridge, atrophy and hyperplasia of the suboccipital musculature, and cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. Scientific Reports. 2023.

- Li C, Yue C, Liu ZC, et al. The relationship between myodural bridges, hyperplasia of the suboccipital musculature, and intracranial pressure. PLoS ONE. 2022.

- Song X, Gong J, Yu SB, et al. The relationship between compensatory hyperplasia of the myodural bridge complex and reduced compliance of the various structures within the craniocervical junction. The Anatomical Record. 2022.

Not a member of the weekly focus?

Join us for the deep dives and all the content of the fundamental Applied Kinesiology course inside the monthly membership of Applied Kinesiology Online!

Cant wait to see you inside of this game we call practice!